The Trapdoor Effect: Why employees quit (and what happens in a market where they can’t)

A ways back, I had the privilege to quit a job. With gratitude for what I'd learned and relationships I'd built, I decided to pack my bags and, for the first time maybe ever, do very little. "I'm gonna get into Pickleball! Woodworking! Archery!" were all things I told myself – and did not do.

Turns out, "do nothing" is pretty alluring, particularly after years of workplace fire drills and constant change.

I wasn't alone. I was part of what became the Great Resignation – and while the job market has shifted dramatically since then, the underlying reasons people disengage haven't changed.

Here's what's different now: from hiring freezes and layoffs to the spectre of AI killing all our jobs and non-stop economic uncertainty, people can't easily leave bad situations. But that doesn't mean they're suddenly satisfied. Instead, they're staying and quietly disengaging – creating a different but equally dangerous problem for organizations.

The question isn't whether people will quit. It's whether they'll contribute their best work while they're stuck.

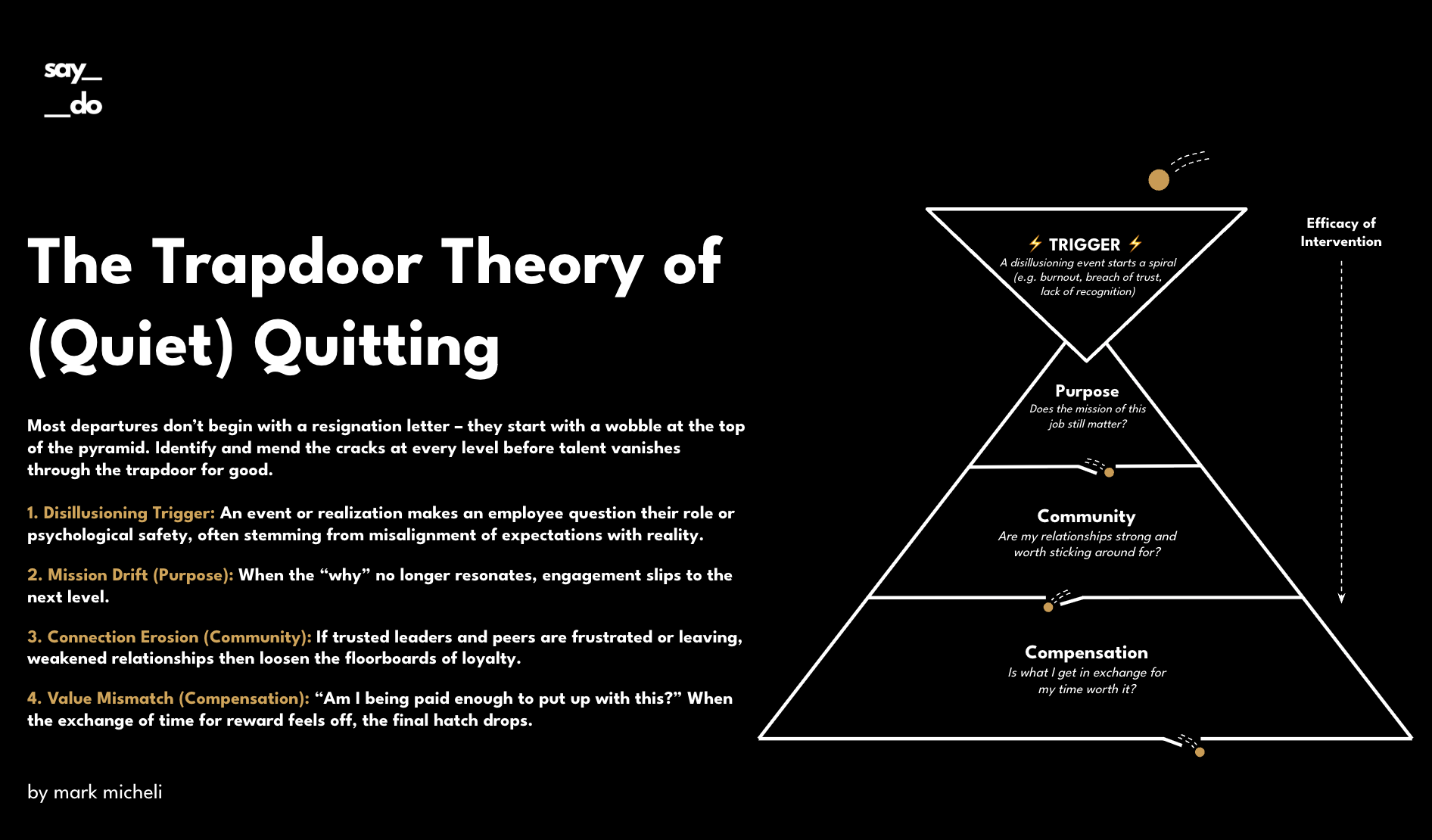

The Trap Door Theory of (Quiet) Quitting

Most departures don't begin with a resignation letter – they start with a wobble at the top of the pyramid. Each person brings their own mix of life stage, experience, attitudes, and values to work. When workplace layers start failing, people fall through successive "trap doors."

During the Great Resignation, they hit bottom and quit. In today's market, they hit bottom and stay – but their engagement, creativity, and discretionary effort disappear.

This makes the framework even more critical for leaders. You can't rely on external market pressure to keep people anymore. You need to identify and mend the cracks at every level before talent vanishes through the trapdoor for good (or stays put in the basement for far too long).

Trapdoor 1: Disillusioning Trigger

(“When Reality Doesn't Match Expectations”)

An event or realization makes an employee question their role or psychological safety, often stemming from misalignment of expectations with reality. This could be a reorganization that changes their scope, a major initiative or project coming to an end, a manager who micromanages after promising autonomy, or discovering the "innovative culture" they were sold is actually a risk-averse bureaucracy (not that I’ve ever experienced that…).

During recent years of constant change, these triggers multiplied. Organizations that acknowledged misalignment and actively recalibrated expectations kept people stable. Those that ignored the wobble at the top lost people to successively deeper layers.

What leaders can do: Regularly audit (or if you’re a human being, check in…) to see if your people's daily reality matches what you promised during hiring. When it doesn't, address the gap explicitly rather than hoping people adjust their expectations downward.

Trapdoor 2: Mission Drift / Purpose

(“When Your ‘Why’ No Longer Matters”)

When the disillusioning trigger creates doubt, people start questioning whether the work itself matters. Does the mission align with their goals and training? Does the work actually make a difference? When the "why" no longer resonates, engagement slips to the next level.

What leaders can do: Don't assume people understand why their work matters. Connect individual contributions to larger outcomes. Make impact visible and personal. When organizational priorities shift, help people see how their role contributes to new directions.

Trapdoor 3: Community & Relationship Erosion (“Um, Where Did Everybody Go?”)

If trusted leaders and peers are frustrated or leaving, weakened relationships loosen the floorboards of loyalty. People fall back on "I'm here because I love the people I work with" – but as dissatisfied colleagues depart, taking institutional knowledge and social connections with them, this layer starts dissolving too.

What leaders can do: When teams change, actively help remaining people through transition. Invest in relationship-building. Create conditions for new connections to form. Don't underestimate how departures of respected colleagues affect those who stay.

Trapdoor 4: Value and Compensation Mismatch ("I’m Not Paid Enough for This S**t")

When the exchange of time for reward feels off, the final hatch drops. This is the worst place to be, and it's where many people find themselves in today's market. When jobs become purely transactional and people feel stuck, dissatisfaction turns to quiet resentment.

What leaders can do: Even when budgets are tight, recognition and growth opportunities matter more than ever. People who feel trapped need to see a path forward, not just a paycheck. Be transparent about constraints (this is a hard time for many organization’s budgets, own that) while finding creative ways to deliver value to employees – even if it can’t be the pay bump they were hoping for just yet.

Why These Trapdoors Matters in a Tight Market

Most retention strategies were designed for a hot job market – perks and benefits to compete for talent. But when people can't easily leave, these surface-level fixes reveal their inadequacy.

People don't just quit jobs. They quit experiences. And when they can't physically quit, they quit emotionally – giving you their presence but not their performance.

In uncertain economic times, you might think you can ignore engagement because people have fewer options. That's exactly backwards. When people feel stuck, the quality of their daily experience matters more, not less.

The New Leadership Reality:

Trapdoor Therapist

The current market creates a false sense of security. Yes, people are staying longer. But are they:

Bringing innovative ideas to problem-solving?

Going above and beyond when challenges arise?

Advocating for your organization with clients and prospects?

Staying engaged during meetings and strategic discussions?

If not, you're paying full salary for partial contribution – and, newsflash, you probably deserve it. Your job as a leader is to, in essence, tie a rope around your waste and lower yourself down to where you can reach an employee or teammate. Extend them a hand, and work creatively to hoist them back up to firmer ground. You are, in essence, a trapdoor therapist – rescuing them, if you can, from the pit disaffection and attrition.

The Strategic Opportunity

Here's what forward-thinking leaders understand: while bad leaders assume market pressure solves engagement problems, you can gain advantage by actually improving workplace experience.

When the market eventually opens up – and it will – your most engaged people will become your strongest advocates and longest-term contributors. Your folks you let linger in the basement will be first out the door, often to competitors.

The trap doors can be reinforced. Even in tight budget environments, improving the "how," clarifying the "why," investing in the "who," and recognizing contributions costs less than the productivity loss from quiet quitting (or outright quitting).

The (Rock) Bottom Line

We're living through uncertainty – economic, social, political, technological (#AI) and more. It’s a lot for anyone, but leaders shouldn't mistake reduced turnover as employee satisfaction. Far from it.

The choice is yours: design employee experiences that maintain engagement even when people feel stuck, or discover that your "retained" workforce has mentally resigned long before the market allows them to physically leave.

In uncertain times, employee experience isn't a nice-to-have. It's what separates organizations that thrive from those that merely survive.